“I see the homeless in the streets, the unemployed. Aren’t those human rights violations as bad as religious persecution?”

-Piotr Rasputin/Colossus

It’s the late 80s, the last days of the Cold War. Reagan’s still in power and the US has been discussing for the past, oh, 45 years or so what Communism and Capitalism are and what they’re for in between wagging their respective dicks at one another and generally making existential threats to most of the human race.

Into that mix, we drop one of the best writer/editors Marvel Comics ever had, Ann Nocenti. Ann Nocenti is a writer whose work I’ve read in bits and pieces over the years and who edited one of my favourite X-Men stories ever, Fantastic Four vs. X-Men (which I need to write something up on) and had a really strange, bubbly, weird run on Daredevil which was very much about how scary, pitiful and pitiable people are when they’ve been driven to violence and because I, sadly, don’t have hard copies of that run or I’d love to do a retrospective of it here.

Quick aside? The only big reason I don’t have it is because if Marvel has that run collected anywhere, I’ve not seen those collections in print. Seriously, I’d really love to see a “Daredevil Visionaries: Ann Nocenti” to sit next to that crap Kevin Smith run which had that “Visionaries” title slapped onto it. Anyway…

So I first picked bits and pieces of the comic we are talking about piecemeal in loose issues of Marvel Comics Presents, an anthology series Marvel ran for a goodly while when I was picking up all my comics from the back issue bins (because you got a lot more comics for your money that way) and helped support and cement my love for the character Colossus. Because my ability to finish the thing was hampered by the fact that my comic shop didn’t have all the issues I’d needed to complete the story, I’d not read it before I moved out here to Sweden where I found the collected edition in the local equivalent of a quarter bin and snatched that thing right up.

And I was so pleased when it was still good.

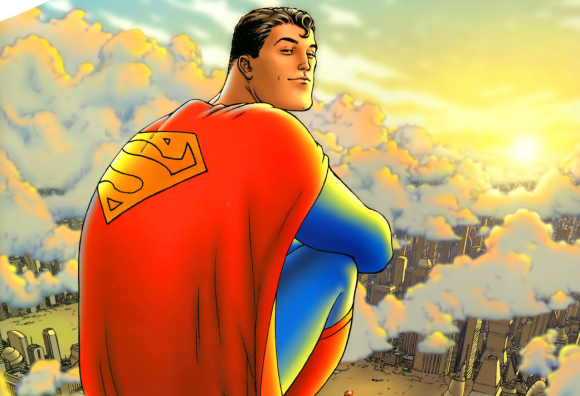

Now because I’m a more writer-centric guy and I’m often guilty of the sin of not giving enough credit to the artists who make the writer(s) sing, I wanna say up front that this story made me fall in love with Rick Leonardi’s work. He’s got (or at least had, his most recent work, Watson and Holmes doesn’t seem very much like the work of his that I knew and loved though is still quite good) a really nice, deceptively simple cartoonish style which lends itself well to the “acting” the characters do throughout and which never descends into the crosshatchy, overdetailed mess a lot of more cartoony styles tend toward. His Piotr Rasputin/Colossus looks appropriately massive and bulky and the action is both easy-to-follow and holds a certain sense of weight to it; I seriously cannot imagine this story being done by anyone else, which is, I should think, the sort of effect any artist should be all about.

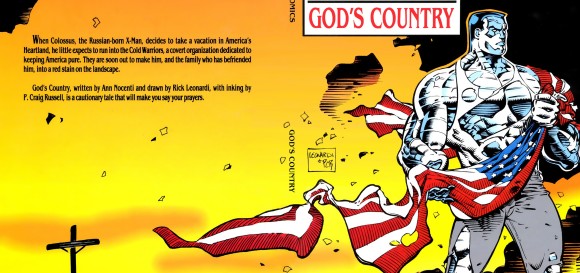

Speaking of course of the story itself, we get to Ann Nocenti whose greatest strength is similarly that no comic she writes feels as if it could have been written by anyone else, largely because she has a perspective about the world and interrogates it with her subjects and vice-versa, giving each run of hers a feeling of a conversation between Mz. Nocenti and the reader. In that vein, God’s Country is about Nocenti interrogating American paranoia in what would turn out to be the last days of the Cold War. It’s a really simple story which is by this point old hat: while journeying across America (as you do when you’re a superhero), X-Men stalwart Colossus crosses paths with a family who have accidentally run afoul of the Cold Warriors (cyborgs tasked with “keeping America pure”) and the story goes back and forth between Colossus and the father of the family, a patriotic and ill-used Vietnam veteran, having explicit discussions of the exploitable freedoms offered by Communist Russia (free access to health care and higher education with restricted freedom of speech or religion and no access to guns) and those offered by the US (freedom of speech, freedom of religion and the right to bear arms with limited access to health care or higher education) and the ways in which both societies have failed to live up to those proffered freedoms in between bouts of fighting off the Cold Warriors and putting a stop to their puppetmaster who may or may not be a super-rich, super-paranoid old fascist or the head of a super-secret arm of the US government.

It’s a nakedly political story interested in deconstructing the myths which prop up the worst excesses of American culture, the right-wing paranoia of The Other and the weird obsession a freedom-obsessed country can have with restricting the freedoms of its citizens and the reasons why that may or may not be a good thing; indeed, it’s actually kind of a subversive story in its way because it questions just how right America’s got things and how well its people could thrive if they took a page or two out of someone else’s book.

And for all comics are, to my thinking, at their best when they’re talking about normal situations in a symbolic or superheroic manner (which is to say cranking shit up to 11.5 and tossing in a lot of explosions while representations of ideas duke it out), you rarely get a discussion of anything that’s even close to that level of nuance; at best, political stories tend to come down either as “America good; not-America scary or bad” or “freedom good, mind-control bad”. Honestly, looking back on the story, it seems like the sort of thing they could only put out in the anthology and then as a “graphic novel” later on because putting that sort of thing in the main book feels like it might ruffle a few too many feathers.

Now, for all the praise I put onto it, I have to admit that it also suffers from some of the weaknesses in Nocenti’s work, which are largely that the dialogue between a lot of her characters feels a bit like the same voice and that one can often tell which side she comes down on even if she gives the “other” side (she’s often less interested in playing between a dualistic two sides but instead investigating the ground between them, which makes the idea of “sides” feel a bit strange in this context) what feels like a fair-ish representation and, if nothing else, only occasionally makes the people who disagree with her point seem unsympathetic—though I suppose that’s just one of the things that happens when you’re trying to Say Something with your work. Even if that sometimes puts me a bit on edge, though, it’s something I can’t really fault her for because it’s so rare that superhero comics really have anything to say that’s not “yay our team; boo their team, let’s all enjoy the bad guy getting beat up”. No matter how in-the-moment schadenfreude-tastic it might be to see the bad guy get his due, in the long run it’s just more people getting hurt because they don’t know better; and knowing that Ann Nocenti finds that as sad and worrying a solution as I do really restores my faith in the genre to this day.